Lubna Chowdhary - Metropolis

Unusual artist who created this insane set of small icon sculptural things

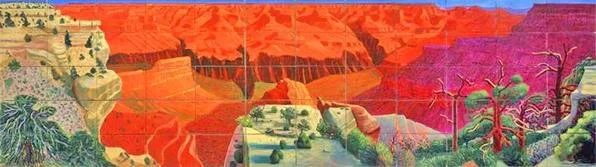

In Appreciation of David Hockney

Short note of appreciation for who Hockney is and what he has represented over his long career.

Agostina Segatori by Van Gogh

‘Agostina Segoatori’ by Van Gogh is a work that I really enjoy thinking about. This piece was painted as he was finding what I consider to be his mature style and in my opinion represented a lot of who van gogh was psychologically as a person